Since a 737 Max 9’s mid-cabin door-plug blew out during a flight on 5 January, Boeing has fought a public battle to clear its name and convince regulators, lawmakers and the public that its jets are safe.

The company has subsequently faced several investigations into how its quality processes failed so substantially that it delivered a jet to Alaska Airlines that lacked four bolts intended to secure the plug in place.

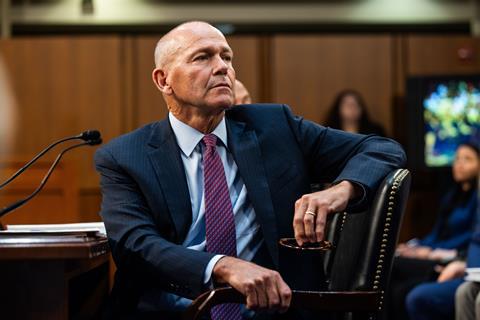

Amid the fall-out, Boeing chief executive David Calhoun faced a dressing down before a Senate committee, and Boeing itself pleaded guilty to federal charges of defrauding the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) during certification of the 737 Max.

Despite all that, there may be reasons to believe Boeing is turning a corner.

After all, the door-plug failure prompted Boeing’s decision to slam the brakes on 737 production and to pursue the acquisition of its most important supplier, Wichita’s Spirit AeroSystems.

More changes are on the way, as the company is now searching for a new chief executive to succeed Calhoun, a move some analysts view as critical to Boeing’s recovery.

Also, Boeing has some positive news to celebrate: on 12 July, the company finally started certification flight tests of its long-delayed 777-9, bringing the widebody’s service entry a step closer.

Some analysts have even squeezed positivity from Boeing’s recent plea agreement with the US Department of Justice (DOJ) – a deal that still requires court approval. The guilty plea, while making Boeing a felon, would at least put the case in the past, helping Boeing turn to a fresh page.

“Boeing’s deal to acquire Spirit AeroSystems and a Justice Department offer to settle a fraud lawsuit could position it to move past a spate of negative news and events, particularly if [second-half 2024] production and deliveries pick up, helping stem cash burn,” Bloomberg Intelligence said in a 9 July report.

Boeing agreed to plead guilty after the DOJ determined, in the wake of the door-plug blow out, that the company had violated a deferred prosecution agreement it signed in 2022.

The government alleged that former Boeing employees misled the FAA about the 737 Max’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), leading the FAA, working on false information, to approve insufficient differences training for pilots transitioning from the 737NG to the 737 Max.

Two 737 Max 8s – a Lion Air jet in 2018 and Ethiopian aircraft in 2019 – crashed after the MCAS system erroneously activated, putting the aircraft into dives from which the pilots were unable to recover. The accidents killed 346 people and prompted the Max’s 20-month grounding.

COMPLIANCE MONITORING

The plea deal would require, if approved, that Boeing pay a $243.6 million fine and unspecified compensation to victims’ families. The company would also be subjected to three years of compliance monitoring.

“We believe this settlement has a limited financial impact for [Boeing] and is an important overhang relief ahead of its CEO announcement,” financial analyst Ken Herbert with RBC Capital Markets said in an 8 July report. “We believe the focus on improving compliance and safety in conjunction with this plea is already in process for Boeing and is consistent with the company’s current efforts.”

The question of who will succeed Calhoun has been an open question since Boeing announced the CEO shake-up in March. Calhoun, who took over from Dennis Muilenburg amid the 737 Max grounding in January 2020, will step down at year-end.

Calhoun, formerly a Boeing board member and General Electric executive, has been supported during his tenure by some Wall Street analysts, viewed as a solid leader doing his best in a difficult situation.

But others, including employees and people close to the company, have long criticised Calhoun, saying he has continued a management strategy that over several decades– specifically since Boeing’s 1997 combination with McDonnell Douglas – has prioritised short-term profits and share price gains above engineering excellence and quality.

Critics fault Calhoun for not taking the bold step of launching a new aircraft development programme, noting that it was his decision not to proceed with the New Mid-market Airplane, a 757 replacement. Detractors also call Calhoun’s 2022 choice to move the airframer’s headquarters from Chicago to Virginia – nuzzling closer to the Washington DC establishment – misguided, saying he passed up a perfect opportunity to engineer a return to Seattle.

Aerospace analyst Richard Aboulafia with AeroDynamic Advisory has insisted Boeing needs a new leader, saying nothing but “regime change” will enable it to execute the type of turnaround required. “Anyone not chosen by Calhoun would be good at this point,” he said.

Regardless, Calhoun’s time is almost up, though who will replace him at year-end remains unclear.

Several names have been thrown around, including GE Aerospace chief Larry Culp and Boeing director and longtime aerospace veteran David Gitlin, both of whom reportedly spurned Boeing’s advances. GE also on 1 July signed a new employment contract with Culp that extends his tenure as its CEO through at least 2027.

Stephanie Pope, a Boeing veteran who succeeded Stan Deal as Boeing Commercial Airplanes CEO on 25 March, has also been floated as a potential successor to Calhoun, though some observers view her as lacking sufficient experience for the top job; others insist Boeing’s next leader should come from outside the company.

For those reasons and others, including the pending acquisition of Spirit, some analysts view Patrick Shanahan, chief executive of the aerostructures firm, as Boeing’s most likely CEO-in-waiting.

Aboulafia has called Shanahan “the perfect man for the job”, adding: “If he can’t do it, this is an impossible situation.”

Shanahan became Spirit CEO in September 2023, succeeding Tom Gentile with a mission to address production and financial woes. Spirit faced looming debt payments and has been losing hundreds of millions of dollars each year on some of its aircraft programmes. Shanahan’s accomplishments came early: in October 2023, he closed a new financially beneficial supplier agreement with Boeing.

A respected manager with supply chain experience, Shanahan previously worked three decades at Boeing, holding positions including senior vice-president of supply chain and operations, senior vice-president of commercial airplane programmes and vice-president of the 787 programme. He was later the USA’s acting secretary of defense and deputy secretary of defense under President Donald Trump.

“Pat Shanahan is known to The Boeing Company,” Calhoun said last year. “We have great respect for his abilities on the shop floor.”

Boeing had owned the business that became Spirit until 2005, when it divested the operation as part of a broad effort to outsource more production.

Boeing’s decision to reintegrate Spirit came in the wake of the 5 January door-plug failure, as it faced immense regulatory and political pressure to finally fix its safety and quality problems.

The plug blew out shortly after the Alaska 737 Max 9 took off from Portland, leaving a massive hole in the side of the aircraft. The pilots landed safely and no passengers or crew were seriously injured.

But the event revealed the extent to which Boeing’s quality problems remained undressed. It resulted from a cascade of issues, including Spirit’s delivery to Boeing of a fuselage with defective rivets.

COMPOUNDING MATTERS

To allow Spirit representatives to rectify the problem, Boeing workers in Renton needed to open the door-plug; they did so and then closed the plug, but failed to secure it with four bolts, according to Boeing and the National Transportation Safety Board.

The incident was another in a long string of Spirit quality lapses, including those that forced Boeing several times in recent years to complete time-consuming inspections and rework of undelivered jets.

On 1 July, Boeing said it had reached an agreement with Spirit to buy the supplier for $4.7 billion in stock. “By reintegrating Spirit, we can fully align our commercial production systems, including our safety and quality management systems, and our workforce to the same priorities, incentives and outcomes – centred on safety and quality,” Calhoun said.

The deal still requires regulatory approval. If it closes, Boeing will suddenly become a much larger company, and one that again produces the bulk of its best-selling jet. Boeing expects the purchase will close in mid-2025.

Acquiring Spirit could help Boeing “eliminate financial stress and operational complexity”, and “facilitate a much-needed boost” to 737 production in the second half of the year, says Bloomberg. “The Spirit purchase can improve Boeing’s ability to effect change at one of the 737’s most-important suppliers.”

Michel Merluzeau, aerospace analyst with AIR, views the pending deal as reflecting Boeing’s conclusion that Spirit drifted too far astray.

“If Spirit had been consistent with quality, if we hadn’t had a January 5th, Boeing might have been happy keeping things the way they are,” he says. “Now Boeing owns the problem… it’s really on them now.”

Merluzeau thinks the acquisition could help Boeing ensure fuselages are defect-free before arriving in Renton, letting Boeing workers there focus more on assembly and less on fixing problems. “It eliminates a lot of that back and forth, and that potential for error,” he says.

PRODUCTION RATE

Prior to the door-plug failure, Boeing had said its 737 production system was running at a rate of 38 jets monthly, and it was aiming to hit 50 per month in 2025 or 2026.

But Boeing significantly hauled back output after 5 January. In June, 737 programme vice-president and general manager Katie Ringgold said the company would like to return to rate 38 “in the next few months”. But she insisted the airframer will not increase production until the system achieves stability.

Merluzeau predicts Boeing will produce about 305 737s this year (25 monthly on average) and more than 460 (38 monthly) in 2025. Factoring in already completed but undelivered inventory, he expects it might ultimately ship 350 737s this year, down from 396 in 2023.

Boeing’s production could be further disrupted by labour troubles involving its largest union, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, which represents some 33,000 employees in the Pacific Northwest, most of them in the Puget Sound region.

The union’s contract with Boeing expires on 12 September, and union leaders are seeking new terms that include 40% raises over three years and a guarantee from Boeing to build its next aircraft in Washington and Oregon. That provision seeks to keep the company from producing its future platform in a lower-cost region like the US Southwest. Boeing in 2021 stopped assembling 787s in Everett and consolidated the widebody’s assembly at its site in North Charleston, South Carolina.

Bloomberg estimates the new contract will cost Boeing an additional $750 million to $1.5 billion annually, inflating production costs by 1.5-2%.

On the development side, Boeing is still working to bring three long-delayed aircraft through certification: the 737 Max 7 and Max 10 variants and the 777-9. As a result, none of those test aircraft will be at the Farnborough show.

Boeing has been reticent to predict when the FAA will clear those jets, as the agency’s increased scrutiny has already pushed the programmes years behind scheduled.

In January, Boeing said it needed another year to redesign the Max 7’s engine anti-ice system, a development that seemingly pushes the certification of both the Max 7 and Max 10 into 2025 at least.

The company has made more progress of late with its 777-9, having received type inspection authorisation (TIA) for the widebody-twin from the FAA and completed its first flight for certification credit.

“With type inspection authorisation for the 777-9, we began certification flight testing with US Federal Aviation Administration personnel on board the aircraft” on the evening of 12 July, Boeing says. “The certification flight testing will continue validating the airplane’s safety, reliability and performance.”

Boeing launched the twin GE9X-powered 777-9 and the broader the 777X programme in November 2013 at the Dubai air show, at the time saying the jet would make first flight in 2019 and be certificated soon after. It has delayed the programme numerous times, due to both development issues and increased scrutiny from the FAA.

The certification flight programme might have just started, but Boeing notes that its four 777-9 test aircraft have completed more than 1,200 flights since the type’s maiden sortie in January 2020.

“The 777-9 flight-test fleet will undergo the most thorough commercial flight-test effort Boeing has ever undertaken. We have also spent significant time working through the required certification deliverables in preparation for TIA,” Boeing adds.

Much about Boeing’s product development strategy after the 737 Max and 777X programmes remains unclear, however; a 737 replacement is expected to in the mid-2030s.

Boeing is now working with NASA to develop the X-66A, a demonstrator aircraft with a unique truss-braced-wing, which will let it evaluate designs and technologies that could inform its next narrowbody. NASA has said the truss-braced design could deliver a 10% efficiency boost compared to today’s narrowbody jets, and that other technologies such as advanced engines could bring the total efficiency gain to 30%.

But developing a 737 replacement is far from the most pressing issue Boeing now finds itself facing. The company must first and foremost prove that the aircraft already rolling out of its factories are safe.

In years past, Boeing often addressed safety questions by issuing boilerplate comments about its commitment to building safe jets.

But in recent months the company has gone much further, making several top executives available to directly discuss safety concerns. The executives went on the record. They backed up their statements with technical details. They answered questions. They put their reputations on the line.

Boeing senior vice-president of quality Elizabeth Lund spent hours in June detailing to reporters changes Boeing made and continues to make to improve safety.

“I am extremely confident that every airplane exiting this factory is safe,” she said. “We are a transparent company who cares deeply about safety.”

Immediately following the 5 January door-plug failure, Boeing ordered its engineering team to complete a 737 critical review to identify systems and components that could theoretically pose major safety hazards.

“We took a list of these systems and… immediately, out of an abundance of caution, put end-of-line inspections in place,” Lund says, noting Boeing completes most of the new inspections after a jet’s first flight but before delivery. “We did this across all airplane programmes… This was an immediate action to ensure that there was no non-conformance that left our system.”

Production team leads also started holding weekly 1h quality meetings with staff to identify concerns or problems, Lund says, adding that one such meeting helped Boeing flag an issue involving heat-shrink material used to protect wires.

Boeing deployed more than 100 employees to oversee fuselages coming out of Spirit’s Wichita production site. The group is charged with ensuring defects are identified and fixed before being shipped. As a result, fuselages arriving in Renton have up to 80% fewer defects, allowing Boeing to move those fuselages much faster through production, Lund says.

Similarly, in April, Boeing made two top engineers available to reporters to discuss an issue involving out-of-specification gaps in 787 fuselages. That issue had been raised by a Boeing whistleblower who told Congress that the gaps could lead to premature structural fatigue and failure, with possibly catastrophic results.

Speaking at Boeing’s North Charleston 787 assembly site, the company’s functional chief engineer of mechanical and structural engineering Steve Chisholm, and vice-president of airplane programmes engineering Lisa Fahl, explained in detail why they believe the gaps do not pose safety concerns.

They reviewed Boeing’s 787 production process in detail and insisted that a wealth of data has demonstrated that the carbonfibre fuselage is incredibly safe – even with out-of-specification gaps. They argue that the gaps, while not conforming to the design, pose no safety concern, and tests indicate the fuselages can retain necessary strength for far more flights than any jet will ever operate.

“There is nothing in these composite joins – in anything we’ve seen, in any testing we’ve done, including the full-scale testing – that is demonstrating there is any concern with the fatigue or durability of this structure,” Chisholm says.