While Beijing’s domestically produced engines are less advanced and require overhauls more than their US counterparts, the improving quality of Chinese powerplants underscores the urgency of developing next-generation propulsion alternatives.

The quality of turbofan engines being produced in China is “catching up” to those developed by Western manufacturers, but for now remain less capable.

That is the assessment of a senior executive at one of the USA’s top jet engine producers, GE Aerospace.

Steve Russell is the general manager of GE’s advanced projects unit, known as Edison Works. That division is responsible for developing the company’s next generation propulsion technology, including a large adaptive cycle turbofan that will power sixth-generation fighters, and small, low-cost engines to propel cruise missiles and uncrewed aircraft.

Many of those innovations are being developed with an eye toward maintaining the USA’s military edge over the rising power of China.

Speaking at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies in Washington, DC on 9 September, Russell said that indigenously produced Chinese engines are closing the performance gap with their American rivals, but still remain inferior.

“They are catching up and we do know that they’re certainly trying to borrow our technology still, like they have in the past,” Russell says.

SINO SUBTERFUGE

Beijing has spent decades conducting a systematic industrial espionage effort to appropriate technology developed in the West for domestic use. That programme has included mandatory technology transfer agreements for US companies doing business in China and the use of agents inside American firms to steal proprietary data.

GE itself was a victim of one such effort. In 2022, an ethnic Chinese US citizen was convicted of conspiring to steal trade secrets related to GE turbine technology used in both aviation and ground-based power generation.

Xiaoqing Zheng was fined and sentenced to two years in US prison, according to the US Department of Justice, which at the time said Zheng “willingly stole proprietary technology and sent it back to the [People’s Republic of China]”.

Beijing now has a number of indigenous military turbofans in various stages of maturity, including the Shenyang WS-10, which is already in widespread frontline service; the higher thrust Shenyang WS-15, two of which are believed to power China’s Chengdu J-20 stealth fighter; and the WS-20, China’s first domestically produced high-bypass turbofan, which has been installed on the Xian Y-20U tanker.

Less mature designs include the AVIC Guizhou WS-19 afterburner, believed to be in development for China’s twin-engined AVIC Shenyang J-35 strike fighter, which is seen as an answer to the US-made Lockheed Martin F-35 stealth jet.

In the interim, the J-35 is powered by the more mature WS-21 – an updated version of an existing Chinese engine developed for the Chengdu/Pakistan Aeronautical Complex JF-17 fighter.

The ability to develop and field a range of engine types demonstrates the significant advancement of China’s propulsion industry, Russell says, noting Beijing was previously reliant on importing powerplants from Russia.

“They’ve got a lot of people and a lot of smart engineers too,” the Edison Works chief says. “They’re working fast, and they have a demand because they’re building many, many jets.”

A 2024 Pentagon report noted both the rapid growth and modernisation within the Chinese air force, even saying that Beijing is “quickly approaching US standards” in key areas like the domestic production and fielding of uncrewed aircraft.

WANING ADVANTAGE

Executives in the USA’s privately-owned defence industry have often criticised the Pentagon for its inconsistent or unpredictable approach to defence procurement, which increases the risk of making costly investments in the development of complex, next-generation technologies.

That challenge is particularly acute in the military propulsion industry, with its low volume and lengthy development timelines.

“I think the government has been a very poor customer, or partner, when it comes to industry,” says Heather Penney, a former US Air Force (USAF) fighter pilot and director of studies and research at the Mitchell Institute, which acts as both a think tank and lobbying entity in support of the air and space forces.

As a result, Penney describes the supply chain supporting US defence production as “fragile”.

“The demand signal has been so capricious that [it] really challenges companies to be able to smooth their workflow, order raw materials, do the long-lead items, [and] care for their [subcontractors].”

Despite those challenges, American engines made by GE Aerospace and its main competitor Pratt & Whitney remain well ahead of their Chinese equivalents, according to Russell.

“Our reliability tends to be still an order of magnitude better than theirs,” he says.

As an example, Russell suggests that Chinese engines have a lifespan in the hundreds of hours before needing an overhaul, versus thousands of hours for a US-made powerplant.

“But they’re getting better and we’re seeing them get better,” he notes. “That’s why it’s important that we take this next generational leap to make sure that we maintain that advantage that we have.”

Washington has several early-stage development efforts featuring advanced propulsion, including the air force’s Boeing F-47 air superiority fighter, the navy’s F/A-XX sixth-generation aircraft, and the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) programme.

The latter effort is providing up to $3.5 billion in research funding for GE Aerospace and P&W to advance prototype designs for a new adaptive cycle engine that could power advanced combat aircraft with a unique mix of high aerodynamic performance and improved fuel efficiency.

GE has dubbed its prototype the XA102, while P&W calls its NGAP powerplant the XA103.

Defence executives and advocacy organisations like the Mitchell Institute note that most of the engines powering Western combat aircraft were developed decades ago during the Cold War.

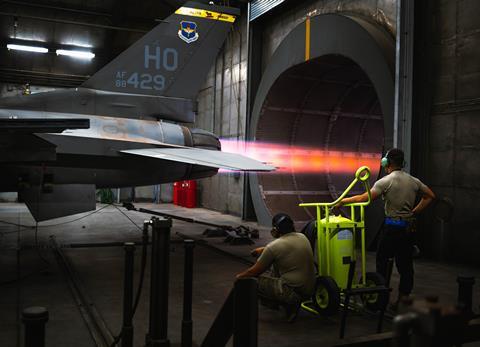

Penney, who flew the single-engined Lockheed F-16, says the quality of American turbofans has always offered US pilots an asymmetric advantage even against industrialised adversaries like the Soviet Union and later Russia.

“We knew that we had reliable aircraft that could outperform what the adversary was doing in many cases, because their engines were not nearly as reliable,” Penney says.

“We really need to be conscientious to ensure that we are still investing within the industrial base to maintain that advantage and stay ahead of the [People’s Liberation Army],” she adds, using the formal name for China’s military.

Although firm details about the secretive NGAP programme are scant, Russell does offer some hints.

While earlier generations of engines were focused on speed and manoeuvrability, the head of Edison Works says the latest development efforts have placed a greater emphasis on range and generating more power for the aircraft’s onboard sensors.

Rather than being purely a stand-in dogfighter like the Lockheed F-22, sixth-generation fighters like the F-47 are envisioned more as advanced hubs for collecting battlefield data and directing groups of uncrewed autonomous support jets to carry out strikes.

“That drives a big part of the requirement,” Russell notes.

“They still want that speed and manoeuvrability,” he adds. “But we certainly want range, and they also want the ability to pull additional power off of the engine… because there’s so many sensors and other systems operating on these complex aircraft now.”

PACIFIC-FOCUSED PROPULSION

Improved range will also be a critical element for next-generation propulsion, particularly if the engines are being designed to enhance the USA’s position against China.

Any conflict in the Western Pacific would almost certainly involve long-range sorties from US bases in the so-called Second Island Chain of Guam and the Northern Marianas Islands to the South China Sea, Taiwan, or even the Chinese mainland.

Guam sits roughly 1,500nm (2,770km) from the centre of Taiwan – well beyond the unrefuelled combat radius of an F-35 and near the edge of total range.

Under an earlier effort to develop an adaptive cycle engine specifically for the F-35, the USAF sought to improve range by at least 35%, while simultaneously delivering improved thermal management and an 18% decrease in acceleration time.

Both P&W and GE Aerospace developed prototypes under the Adaptive Engine Transition Program, neither of which were ultimately adopted.

GE claimed its XA100 design would have offered the F-35 20% more thrust and 30% greater range.

Both propulsion suppliers say their learnings from the AETP contract are now being applied to the NGAP engine effort.

American defence and intelligence officials have concluded that China aims to be militarily prepared to forcibly retake Taiwan by 2027, although it is not believed that an order to do so has yet been given.

In February, the USA’s top military officer in the Indo-Pacific declared that China is now actively rehearsing for such a campaign in the waters and skies around Taiwan.

When it comes to advanced propulsion, Russell says the USA’s engine suppliers are ready to ramp up.

“We have the teams in place, we’ve got the supply chain ramping up,” he says. “We just need the go signal and we’re ready.”